Family

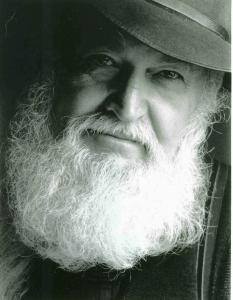

Utah Phillips

Thursday, March 5, 2009

In a matter of a few minutes Anne Feeney phoned me from an airport in Houston. Al Grierson's "Lonely Deadhead Box-Car" was playing on Random on my iPod. After our conversation, I went to check my email. Jim Page was singing "Anna Mae." I had an email from Jim. I have pasted it below. As I read it Utah sang "All Used Up." As I responded to Jim's Email Arlo Guthrie sang "Hobo's Lullaby."

> In the night of May 23, 2008, Bruce Duncan Phillips died in great peace,

> asleep in his bed in Nevada City, California, with his wife Joanna by

> his side.

>

> Amazingly, at the very same instant that the scholar Bruce Phillips

> finally discovered his angle of repose, U. Utah Phillips flagged a

> westbound freight train. Yes, a mighty fast rattler, on a long

> west-bound track. He needed no ticket, he was welcomed on board.

>

> The immediate family and neighbors of Bruce Phillips, along with any

> Wobblies who happen to be passing through, are gathering in Nevada City

> to do all the things that must be done. Please give them the quiet

> respect they so need right now.

>

> But you can wave "So Long!" to Utah when that train moves west. Hey,

> hear the whistle? He's passing by right now!

Dear Friends -

Here is John McCutcheon's eulogy for Utah which was

offered at the memorial celebration in Nevada City.

My friends, my sisters and brothers….Fellow Workers!

When Joanna called me last week and asked me to speak today about Utah's place in folk music I realized I would have to start out with a confession. One that Utah would have made. One that will probably come as no surprise to you all. It was never about folk music. Oh, don't get me wrong. Utah Phillips was and is one of the mighty pillars of American folk music. He left us a body of songs that will be sung for millennia to come. He was an exquisite guitarist, something that those who came to Utah late in his life might never have known. He entertained us and incited us and confounded us and pissed us off his entire life. But it was never about folk music. It was all about possibility.

First time I saw Utah I was 19 years old and attending my first folk festival. There he was, as usual, talking about the invisible among us: the hobos and bums and tramps, the makers of history ignored by historians, the writers of songs you rarely hear, the characters who frequent the fringes of this world. They were the center of his. He was railing against the bosses, inciting us all to rise up, instructing us in the fine art of freighthopping, feeding us copious shovels of mooseturd pie and playing like a devil and singing like some sort of broken-winged angel. I remember thinking, "I've never seen anyone like him!"

Music was that excuse…that shill, he'd call it…that suckered the public into little dark rooms with him and then sent them back out from those rooms into a world that would never…could never…be the same. They'd been on a ride that they hadn't expected and maybe didn't even want. But live performance…and Utah understood this better than most…was about coming out the other side a different human being. Changed, in however small a way, and seeing life through a new lens. One that included the invisible…past, present and future. It was all about possibility.

It was about the possibility that maybe…just maybe…this was all about more than applause and a paycheck. That maybe it was about gathering people together for a couple of hours and have them leave longing for that kind of connection beyond those two, stage-lit hours. It was about the possibility of community.

And the leap from possibility to reality is action. He stayed in the houses, slept on the sofas, ate at the tables, lingered long after the encore. He was creating a template for the folk music community. He was creating a template for America.

And that sense of possibility informed how he related to his comrades in the Trade. In a field in which the Industry bids us treat other musicians as competition, he fostered cooperation. Some of the first work we did together was the nascent effort to organize folk musicians in this country. To provide them with the dignity, the respect and the benefits that workers in other trades fought for, won, defended, and enjoyed. Benefits that, alas, come to fruition just a little too late for Utah to take advantage of.

But like all his work, the political was the personal. He knew that each fellow worker was, first and foremost, a human being. At the Vancouver Folk Festival he bypassed one of the legendary post-concert performer parties to organize a father's shower for me when he heard my first child was about to be born. He was the first to volunteer for a benefit to aid musicians felled by illness or hard times. He walked his talk and leaves a trail future folksingers ignore at their…and our…peril.

The astronomer, Carl Sagan, opined that if Jesus, when he ascended to heaven, were traveling at the speed of light, he would still be in our galaxy.

And every human song ever sung…from the first musician's instinctive caterwaul to Utah's last musical breath…traveling at the relatively glacial speed of sound, is still here: resonant and real.

Death doesn't rob us of our voice, then, it gives us a place in a great cosmic choir, one that means Utah is finally singing in time w/Joe Hill and Big Bill Haywood, with Haywire Mack McClintock and Mother Jones. That Woody Guthrie is introducing himself, at long last, to an heir he never had the chance to meet. And Aunt Molly Jackson is asking when that wonderful young hussy, Rosalie Sorrells, is finally gonna make her way up yonder. And that Utah is confounding everyone with even more bullshit than he ever had a chance to spin down here.

"The long memory is the most radical thing in America," he often reminded us. He was our community's genealogist: crafting our family history before our eyes. He named our ancestors and told us about who we are. And exhorted us to think and act about who we might be. It was all about possibility.

I last spoke to Utah on his birthday, just a few weeks ago. And I last saw him this past January at our annual, post-KVMR concert breakfast. As usual, he was talking about the invisible among us, railing against the bosses, inciting me to rise up yet again, serving up copious amounts of mooseturd pie (version 2.0) and plotting about making non-violence the focus of the rest of his life's work. "We need to do this, John. We need to do this," he implored. I remember thinking, "I'll never see anyone like him again."

So, Fellow Workers, he has gathered us here together one more time. And we stand here, pregnant with possibility, his community, our community, a template for America. We gather here to commend the tired bones of our dear comrade to the earth. Go to sleep you weary, hobo. You earned your rest. There are other hands to take up the plow, the hammer and the guitar. You are now a part of that Long Memory. Yet, somehow, I know your rest will not be a quiet one. When Californians feel the very earth beneath their feet tremble and move, there will be a new understanding of why that might be. Death is not the end. It's all about possibility.

> In the night of May 23, 2008, Bruce Duncan Phillips died in great peace,

> asleep in his bed in Nevada City, California, with his wife Joanna by

> his side.

>

> Amazingly, at the very same instant that the scholar Bruce Phillips

> finally discovered his angle of repose, U. Utah Phillips flagged a

> westbound freight train. Yes, a mighty fast rattler, on a long

> west-bound track. He needed no ticket, he was welcomed on board.

>

> The immediate family and neighbors of Bruce Phillips, along with any

> Wobblies who happen to be passing through, are gathering in Nevada City

> to do all the things that must be done. Please give them the quiet

> respect they so need right now.

>

> But you can wave "So Long!" to Utah when that train moves west. Hey,

> hear the whistle? He's passing by right now!

Dear Friends -

Here is John McCutcheon's eulogy for Utah which was

offered at the memorial celebration in Nevada City.

My friends, my sisters and brothers….Fellow Workers!

When Joanna called me last week and asked me to speak today about Utah's place in folk music I realized I would have to start out with a confession. One that Utah would have made. One that will probably come as no surprise to you all. It was never about folk music. Oh, don't get me wrong. Utah Phillips was and is one of the mighty pillars of American folk music. He left us a body of songs that will be sung for millennia to come. He was an exquisite guitarist, something that those who came to Utah late in his life might never have known. He entertained us and incited us and confounded us and pissed us off his entire life. But it was never about folk music. It was all about possibility.

First time I saw Utah I was 19 years old and attending my first folk festival. There he was, as usual, talking about the invisible among us: the hobos and bums and tramps, the makers of history ignored by historians, the writers of songs you rarely hear, the characters who frequent the fringes of this world. They were the center of his. He was railing against the bosses, inciting us all to rise up, instructing us in the fine art of freighthopping, feeding us copious shovels of mooseturd pie and playing like a devil and singing like some sort of broken-winged angel. I remember thinking, "I've never seen anyone like him!"

Music was that excuse…that shill, he'd call it…that suckered the public into little dark rooms with him and then sent them back out from those rooms into a world that would never…could never…be the same. They'd been on a ride that they hadn't expected and maybe didn't even want. But live performance…and Utah understood this better than most…was about coming out the other side a different human being. Changed, in however small a way, and seeing life through a new lens. One that included the invisible…past, present and future. It was all about possibility.

It was about the possibility that maybe…just maybe…this was all about more than applause and a paycheck. That maybe it was about gathering people together for a couple of hours and have them leave longing for that kind of connection beyond those two, stage-lit hours. It was about the possibility of community.

And the leap from possibility to reality is action. He stayed in the houses, slept on the sofas, ate at the tables, lingered long after the encore. He was creating a template for the folk music community. He was creating a template for America.

And that sense of possibility informed how he related to his comrades in the Trade. In a field in which the Industry bids us treat other musicians as competition, he fostered cooperation. Some of the first work we did together was the nascent effort to organize folk musicians in this country. To provide them with the dignity, the respect and the benefits that workers in other trades fought for, won, defended, and enjoyed. Benefits that, alas, come to fruition just a little too late for Utah to take advantage of.

But like all his work, the political was the personal. He knew that each fellow worker was, first and foremost, a human being. At the Vancouver Folk Festival he bypassed one of the legendary post-concert performer parties to organize a father's shower for me when he heard my first child was about to be born. He was the first to volunteer for a benefit to aid musicians felled by illness or hard times. He walked his talk and leaves a trail future folksingers ignore at their…and our…peril.

The astronomer, Carl Sagan, opined that if Jesus, when he ascended to heaven, were traveling at the speed of light, he would still be in our galaxy.

And every human song ever sung…from the first musician's instinctive caterwaul to Utah's last musical breath…traveling at the relatively glacial speed of sound, is still here: resonant and real.

Death doesn't rob us of our voice, then, it gives us a place in a great cosmic choir, one that means Utah is finally singing in time w/Joe Hill and Big Bill Haywood, with Haywire Mack McClintock and Mother Jones. That Woody Guthrie is introducing himself, at long last, to an heir he never had the chance to meet. And Aunt Molly Jackson is asking when that wonderful young hussy, Rosalie Sorrells, is finally gonna make her way up yonder. And that Utah is confounding everyone with even more bullshit than he ever had a chance to spin down here.

"The long memory is the most radical thing in America," he often reminded us. He was our community's genealogist: crafting our family history before our eyes. He named our ancestors and told us about who we are. And exhorted us to think and act about who we might be. It was all about possibility.

I last spoke to Utah on his birthday, just a few weeks ago. And I last saw him this past January at our annual, post-KVMR concert breakfast. As usual, he was talking about the invisible among us, railing against the bosses, inciting me to rise up yet again, serving up copious amounts of mooseturd pie (version 2.0) and plotting about making non-violence the focus of the rest of his life's work. "We need to do this, John. We need to do this," he implored. I remember thinking, "I'll never see anyone like him again."

So, Fellow Workers, he has gathered us here together one more time. And we stand here, pregnant with possibility, his community, our community, a template for America. We gather here to commend the tired bones of our dear comrade to the earth. Go to sleep you weary, hobo. You earned your rest. There are other hands to take up the plow, the hammer and the guitar. You are now a part of that Long Memory. Yet, somehow, I know your rest will not be a quiet one. When Californians feel the very earth beneath their feet tremble and move, there will be a new understanding of why that might be. Death is not the end. It's all about possibility.